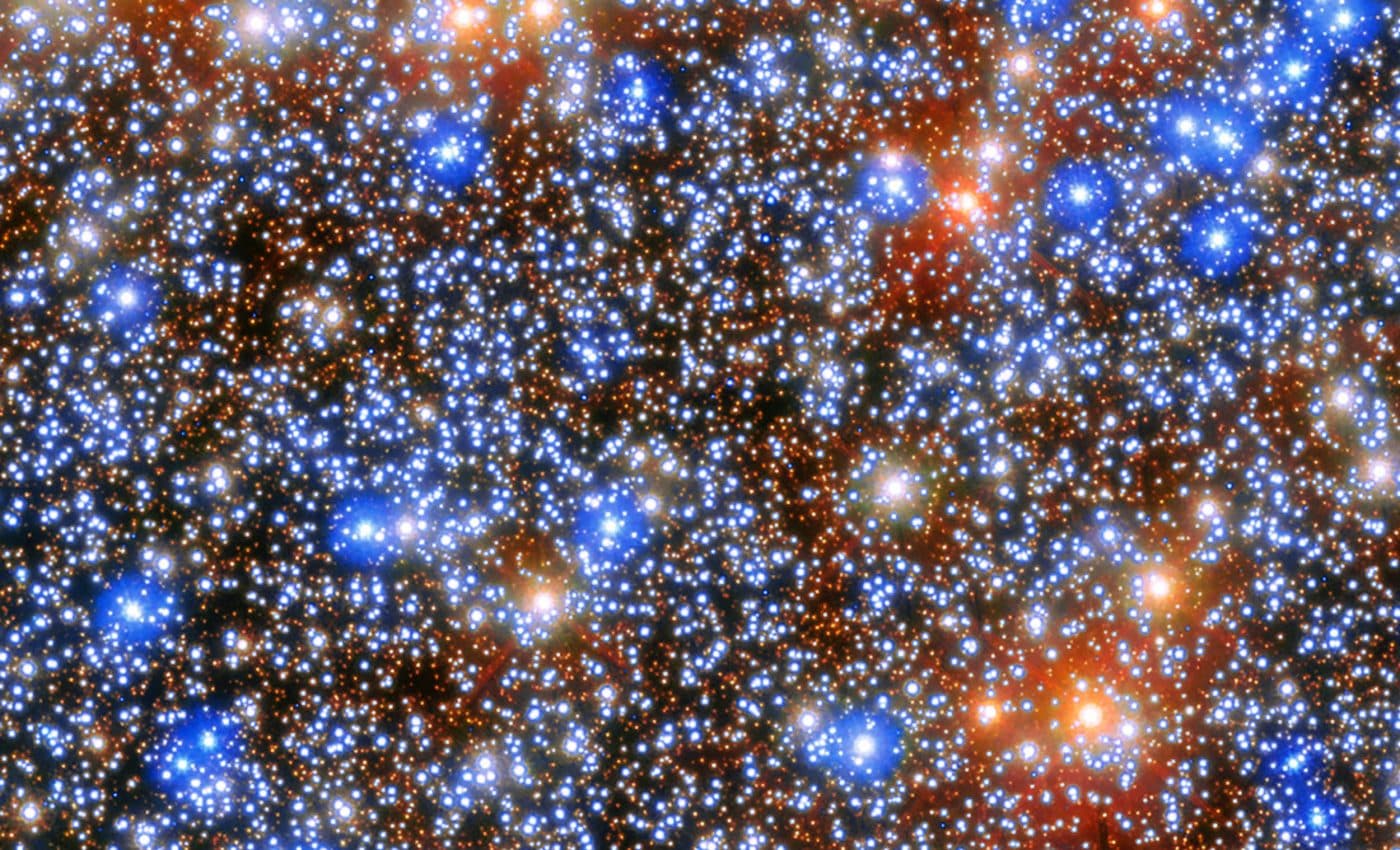

Omega Centauri is a celestial marvel that dazzles as a colossal assembly of 10 million stars and it appearing as a fuzzy spot in the night sky from our Southern hemispheres. With a modest telescope, it doesn’t seem much different from other globular clusters. However, this ordinary view belies an extraordinary discovery.

Anil Seth from the University of Utah and Nadine Neumayer from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy have discovered a cosmic mystery that has puzzled astronomers for ages. In an astonishing breakthrough, these experts have uncovered an almost elusive intermediate-mass black hole in Omega Centauri.

“This is a once-in-a-career kind of finding,” exclaimed Seth. “I’ve been thrilled about it for nine straight months. Every time I think about it, I can barely sleep. Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence and this is truly extraordinary.”

Astronomers have long speculated about an unseen mass at Omega Centauri’s core inferred from the varied movements of stars within the cluster. Yet, distinguishing whether these were due to an intermediate-mass black hole or a collection of stellar black holes was a persistent challenge.

This black hole evading detection until now has remained an enigma. After months of meticulous analysis of stellar motion, the researchers finally identified “high-speed stars,” confirming the intermediate-mass black hole’s presence.

Neumayer remarked that this black hole is the closest massive one known that located about 18,000 light-years from Earth whereas our Milky Way’s supermassive black hole is about 27,000 light-years away.

Black holes are very diverse. According to study co-author Matthew Whittaker they can be compared to Earth’s creatures. Stellar black holes are like ants and spiders that is common yet hard to see. Supermassive black holes are easily noticeable and immensely powerful. The elusive intermediate-mass black hole is akin to Bigfoot—rarely spotted and highly sought after.

To get the Omega Centauri’s formation history, Seth and Neumayer initiated a project to search for fast-moving stars, a “proverbial smoking gun” that would reveal the black hole’s mass. This difficult task was led by Maximilian Häberle who is a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute and he described it as searching for a needle in a haystack.

Leave a Reply